Summer 2023

Building Inspiration

Dawn Stevens, Comtech Services

Dawn Stevens, Comtech Services

Growing up, I had a pretty large collection of Lego blocks. My dad traveled a lot for work and Legos became the de facto “guilt” gift I received when he would come home. My brother and I would build all sorts of structures, crafts, and creatures from our imagination, spending hours of play in the guest room that served as our Lego home world.

Eventually, for a period of time, I outgrew the Lego sets in favor of “more mature” interests, never dreaming that they would once become a passion for me as an adult, and certainly not that they would become a tool for my career. However, several years back I went home to claim the Lego blocks of my youth to use as manipulative devices in the courses I was teaching, and I have since then expanded our definition of “office supplies” to add newer, more vibrant, and more advanced pieces to our inventory.

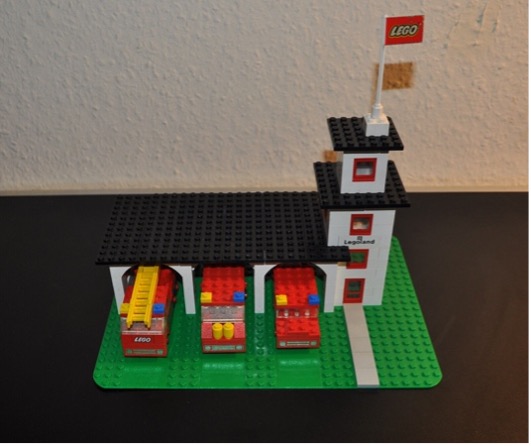

As Lego began to introduce their prescribed building sets, we added more realistic items to our repertoire as well. I got all the fire stations and my brother the police stations.

My dad unknowingly set the stage for my future by giving me a firm foundation in taxonomy development – in particular, classifying and sorting pieces. Before I could actually play with my new blocks or build the new set, we first sat down with a spreadsheet…at the time, physical, handwritten pieces of paper…and recorded the new bricks in my collection. (Ultimately, this ancient document served as a way for adult me to claim the bricks that were mine, which had at some point, after we had both moved away and started our own households, been mixed together with my brother’s.) We sorted bricks by color and size, and eventually as new types of bricks kept showing up that didn’t fit these categories, by any number of other categories and names we could come up with, which I must confess included terms like “thing-a-ma-gig,” and “weird, double-slanted, doo-dad.”

From the toys of my youth, I learned basic taxonomic rules that readily apply to content strategy:

- If the term isn’t meaningful and memorable, you will have a hard time using it when adding new items in the future. Many times my dad and I recognized a new brick as being similar to something we had previously categorized, but we couldn’t figure out what we had named it before, and so we created even more terms.

What would you call this piece? (It’s a rubber band belt holder.)

- Inventorying and retrieval are two different concepts, which don’t necessarily support each other. While our categories were mostly good for inventory (what do we have), they were often not helpful for piece retrieval (what do I need right now).

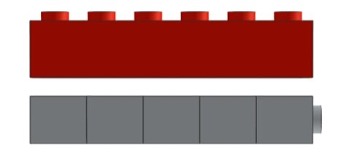

A bin of entirely red bricks is certainly easy to sort, but when trying to find a red 1×1 round, it’s better to have a bin of all 1×1 rounds; it’s easier to find the right color amongst a collection of other colors than to find the right piece in a vast array of difference pieces.

- You don’t need to apply all the categories you’ve come up with to every single piece. Some pieces just need color and size to be fully described; others need a much more robust set of keywords. From the retrieval side, you only need to get to a general right vicinity; pieces don’t have to be defined to such a point that there is only one type that meets all the keywords defined. It’s enough to apply only a few descriptors until your eye can easily find what you are looking for amongst the similar, but not exact, pieces with which they are sorted.

- Throwing unique pieces into a general “other” category just gives you a really big pile of things that are difficult to find.

- The order in which you sort things matters. Sorting pieces that are all part of a specific set together with batches of other general pieces makes it far more difficult to find what you need for that specific context; it’s far better to keep the set together and then sort the pieces by your other categories.

As Lego continues to release more and more complex sets, they continue to apply this concept; sorting first into bags numbered by step, rather than by similar pieces as was done in my early sets.

- There will always be new things that require new categories or terms. Through the years, new sets required that we add entirely new categories (like Space) and new values to our categories (like purple to Color). As new pieces were introduced, we had to decide how exact we needed to be – is it important to distinguish between green and green tinted bricks?

The inherent characteristics of Lego blocks not only make them a great tool in teaching taxonomies, but a common reference for explaining structured authoring and reusability. We’ve probably all heard comparisons to Lego in discussions about breaking content into component pieces with similar structures so that they can be repositioned and used for a variety of purposes. In fact, Lego says that just six 2×4 blocks can be combined in 918,103,768 different ways.

When you visit Lego headquarters in Denmark, in fact, they give you a package of six bricks and a diagram for your own unique configuration. (Some workers also challenge you to build the configuration without taking the pieces out of the bag.)

When you visit Lego headquarters in Denmark, in fact, they give you a package of six bricks and a diagram for your own unique configuration. (Some workers also challenge you to build the configuration without taking the pieces out of the bag.)

Lego designs pieces in a way that you can count on for compatibility:

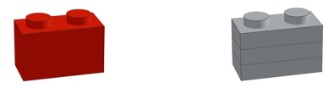

- Standard bricks are three times as high as a flat base.

- The width of two studs is the same as the height of five stacked plates leaving the studs exposed.

- Six studs wide is the same as the height of five stacked bricks, with the studs exposed.

- There is a small tolerance gap designed between LEGO bricks that is needed to keep the parts from getting stuck to each other when you build with them.

Even-studded standard bricks fit on hollow studded Duplo’s, allowing your children to continue to use their first Lego sets in new creations as they age.

As I add more Lego sets to my collection, I am continually amazed by the repurposing that Lego achieves!

Who knew that a frog could also serve as the flower buds on a bonsai tree or the tops of the waves in a recreation of The Great Wave by Katsushika Hokusai?

At our annual ConVEx conference this year, we used Comtech’s collection of Lego blocks to take a closer look at how they illustrate our world of XML schemas or document type definitions (DTDs). Participants built one of four types of objects and worked to define a Brick Type Definition (BTD) so that others could create similar items according to their specification. Groups created environmental definitions about the objects that were welcome at their table, and individuals searched for places where their creations could live. People with similar object types were merged together and found they also had to merge their BTDs so that all their different objects were compatible with each other and fit into the defined environment.

From the exercise, participants gleaned the following principles:

- A set of common rules is imperative when creating an overall environment

- Everyone will not come up with the same rules when left to their own devices.

- Your creation can be a perfectly fine object when standing on its own, but it may stick out when compared to the others.

Selection of creations in the “Transportation” creation type.

Selection of creations in the “Transportation” creation type.

- You must find a good balance of rules to maximize reusability. Too many rules may severely restrict what you can build, limit creativity, and exclude too many things from your environment. Too few rules, while inclusive, eliminates consistency and makes it difficult to find a common thread.

- The way rules are expressed, semantically or syntactically, can affect consistency, but also creativity.

- For example, indicating that a flying creature needs wings (semantic), allows much more creativity than saying the creature’s wings must be built with a 2×8 plate (syntactic).

Selection of creations in the “Creature” creation type.

Selection of creations in the “Creature” creation type.

- Not every object will be reusable. Some environments may require the development of specific content.

- It is possible to normalize objects to fit more places while still maintaining their character. Identify and remove distinctions (at all levels) that are not meaningful or prevent certain groups from creating their required content.

- Isolating differences, modularizing your creation, and allowing for substitution can make items reusable in previously limiting environments. A creature with a sword can leave its sword behind in a peaceful community. Red doors might be substituted for black ones to be allowed into a monochromatic environment. A trailer may be unhitched for the primary vehicle to meet a size limit.

Selection of creations in the “Structure” creation type.

Selection of creations in the “Structure” creation type.

- We need limits to the number, size, shape, purpose of the components. You do not have to use every component that’s available to get the output you need. A standard may include many components that don’t apply to your situation. Remove them to eliminate the temptation to use them and disrupt your environment.

- Sometimes you may not have all the pieces you need. Consider what components you might source from other groups.

In short, we must have a strategy for how we are going to use the components of our structured authoring. Without one, we may find ourselves drowning in a repository of pieces, overwhelmed by endless possibilities.

Drowning in your repository of components? We can help. Give Comtech a call.

About the Author: Dawn Stevens is CIDM’s Director and President of Comtech Services. She has over 30 years of practical experience in virtually every role within a documentation and training department including project management, instructional design, writing, editing, and multimedia programming.